We now have four granddaughters. The older two are eight and seven. The younger two were born during the Covid crisis, just five and three months ago. For the older two, much of the conversation centers on questions about the opening of the school year. But all of them are fortunate to have comfortable homes and parents with secure jobs that can be managed remotely. Many other children in this country are not so fortunate.

Recent data show that some 14 million children are food deprived. It’s a shocking statistic for the richest nation in the world. Even before Covid, child poverty was a widespread but little discussed issue. As a 2019 report on American poverty in the Economist magazine commented, children neither vote nor hire lobbyists.

Our kids pay the price for our selfish choices. In the rush to reopen bars and other “essential” amenities, and to party with large groups, the potential impact on schools was largely ignored. As a result, millions of children face the prospect of having to study remotely. Not surprisingly, children in low-income families are most likely to suffer significant loss in learning due to the school closings as their access to Wi-Fi and or laptops is often more limited. Higher-income parents are more likely to be able to give at-home support since one or more may be able to work from home or have flexible hours. In addition, for many children living in poverty, a school breakfast or lunch may be their only substantial meal of the day.

Housing and childcare are the biggest constraints on the household budgets of poor people. This country has grossly underinvested in pre-K education. According to a 2019 report by the National Institute for Early Education Research 2019, just over 5% of three-year-olds are enrolled in early childhood programs and one third of four-year-olds. Just ten states provide state funded pre-K to more than 50 percent of four-year-olds. Spending levels vary widely. Washington, DC, spends $5,170 per child and North Dakota $777. Wages for early childhood teachers tends to be low. Yet Nobel Laureate James Heckman reckons that high quality early education can generate more than $7,000 for every dollar spent.

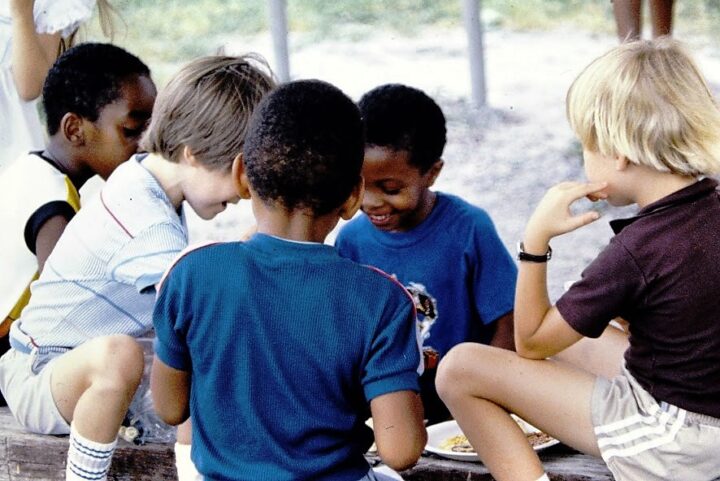

African American and Latino children are also much more likely to attend schools which have a high percentage of minorities from low-income families. Indeed, over the past 40 years, schools have actually become more segregated. More than half the nation’s children are in racially concentrated schools where over 75 percent of students are either white or nonwhite.

According to Tom Pettigrew, a leading social psychologist and researcher, “integration has not failed; America has failed integration.” In 2004, I attended a forum of scholars and practitioners to consider intergroup relations fifty years after Brown v Board of Education. In his keynote address, Pettigrew highlighted a 1974 Supreme Court ruling that allowed suburban schools in Detroit, Michigan, to be protected from a metropolitan desegregation plan, setting the pattern for a national trend for local jurisdictions to act as “racial Berlin walls.” Since then, we have seen a “persistent use of non-racial reasons for anti-black attitudes and behavior.”

As the Economist notes in its report, a 2014 study by Rucker Johnson, a public-policy professor at the University of California at Berkeley, found that five years in desegregated schools boosted incomes by 30% later in life; and exposure to integrated elementary schools reduces the chance of incarceration by 22%. It also raises life expectancy. Unfortunately, says the report, the national trends in income segregation between the rich and the poor are heading in the opposite direction – increasing 15% from 1990 to 2010, and 40% within large school districts. And while the overall percentage of Americans living in poverty has decreased, thanks to federal programs started in the 1960s, the number living in concentrated poverty has increased by 57% since 2000.

It’s important to remember that the reasoning behind the Brown case was not just about black kids being able to go to school with white students. Fundamentally, it was about having access to equal resources and similar opportunities which could only be achieved through integration.

In 2014, as we marked the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision, I wrote a blog highlighting the resegregation of America’s schools as documented by Jonathan Kozul in The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America. In a 2007 ruling, the Court effectively buried Brown by outlawing even voluntary initiatives to create racial balance, as for example in Seattle and Louisville. Justice Stephen Breyer, in a scathing dissent, likened the inequality in our schools to “a caste system rooted in the institution of slavery and 50 years of legalized subordination.”

Most school districts focus on improving their schools by raising academic standards and holding teachers and students accountable through testing and promoting private-sector competition. But Genevieve Siegel- Hawley argues that the labyrinth of school-district boundaries divides students – and opportunities – along racial and economic lines. In When the Fences Come Down: Twenty-First Century Lessons for Metropolitan School Desegregation, she uses four case studies to demonstrate the need to overcome the educational divide between cities and suburbs by also addressing factors such as segregated housing.

This is not a “Southern problem.” Contrary to what one might expect, the most segregated schools are in the Northeast, with New York heading the list. Without parental participation, our schools are likely to continue in this divided state. Legislation and court orders play their part, but people vote with their feet and will move – if they are able – to wherever they believe their child has the best chance of success.

In preparing her book White Kids: Growing up with Privilege in a Racially Divided America, Margaret Hagerman conducted a two-year study in a Midwest city of 30 students between the ages of 10 and 13, and returned a few years later when the kids were in high school for a follow-up study. In a discussion about her book with Inside HigherEd she said that one of the most important lessons from her research was that actions speak louder than words. “Whether parents use color blind language (‘We don’t see race’) or color conscious language (‘We are antiracist’), what they say often matters far less than what they actually do — and specifically, what they do to design their child’s social environment. When parents move to a segregated white neighborhood because the kids in the integrated neighborhood are ‘too rough,’ or when they believe a ‘good’ school is a whiter school, or when the only people in a child’s life are also white with the exception of the economically marginalized black and brown people at the soup kitchen whom they are told they must help ‘save,’ white children notice and develop understandings of not only the position of others in society but also of themselves — they learn about their own power and privilege through observing and interpreting this world around them.”

The Economist report notes that federal programs remain fixated on the problems of the past, namely the needs of the elderly and the working poor. While these needs are still present, children are now the likeliest group to experience poverty and America does much worse than other industrialized countries. According to the report, “More than a fifth of America’s children remained poor after government benefits compared with 3.6% of Finnish children. When Michael Harrington wrote ‘The Other America’ in 1962, which helped to spark Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, the elderly, hobbled by medical and housing costs, were the poorest age group in the country.” Today, overall, with the advent of programs such as Medicare, and Social Security, “there is no age better served.” Data show that 48 % of elderly Americans would have been poor without the safety net. After taxes and transfers, that figure is down to 14%. With significant exceptions (especially during this pandemic), most of the baby boomer generation – myself included – appear to be in a more stable and secure financial situation than younger generations.

The Economist also notes the “reluctance among many liberals to discuss the impact of family structure on child poverty.” Patrick Moynihan’s controversial 1965 report pointed to out-of-wedlock births as a leading cause of black poverty. At the time, around a quarter of black children were born out of wedlock. Today that share is about 70% for black children, more than 50% for Hispanics and almost 30% for whites – all concentrated among poorly educated mothers. The official poverty rate for the children of single mothers is 39%, compared with 8% for those living with married parents.

In a 2016 blog I referred to Robert Putnam’s book Our Kids: An American Dream in Crisis. Putnam acknowledges that changes in the economy are important contributing factors in the weakening of family structures. Unemployment, underemployment and poor economic prospects discourage marriage and stable relationships. But he also notes that gender and sexual norms have changed: “For poor men, the disappearance of the stigma associated with premarital sex and nonmarital birth, and the evaporation of the norm of shotgun marriages, broke the link between procreation and marriage. For educated women, the combination of birth control and greatly enhanced professional opportunity made delayed childbearing both more possible and desirable.”

Our most basic duty is to ensure that every child has access to good quality education in a safe school environment, a stable home life, health care and a clean environment. This needs to be at the top of the agenda for any administration. But as individuals, we all have a responsibility to play our part and make choices that demonstrate our care for the most vulnerable and precious members of the national community. Let’s put children first.