In an op-ed column in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Paul Williams writes about Collie Burton III who died November 11, just six days before he would have turned 94. “Whether he was hosting international gatherings, helping to create a more equitable voting system in Richmond or bringing Black and white clergy together to break bread, Collie devoted his life to positive change, locally and globally.”

As a founding member of the Initiatives of Change program Hope in the Cities, his work took him and his wife, Audrey, beyond Richmond and the US to Zimbabwe, South Africa, Fiji, New Zealand, and Europe. Williams writes, “His behind-the-scenes activism wasn’t the type that made headlines. But it forged relationships that paved the way for Richmond, a historically insular and hidebound city, to openly confront its painful past within a global framework.”

Burton was an associate director of the Richmond Urban League, a member of the NAACP and the Richmond Community Action Board that supported the Richmond Tenant Organization. At the Urban League he helped facilitate Richmond’s transition from at-large voting to a nine-district election system which in 1977 led to the first Black majority on the city council. Rev. Sylvester “Tee” Turner, a longtime friend and colleague, told Williams, “Collie, to me, was a seasoned warrior. And he didn’t waste his bullets. He didn’t waste his time with things that were not substantive…He was always pursuing a cause that was healthy and beneficial to the community he was serving.”

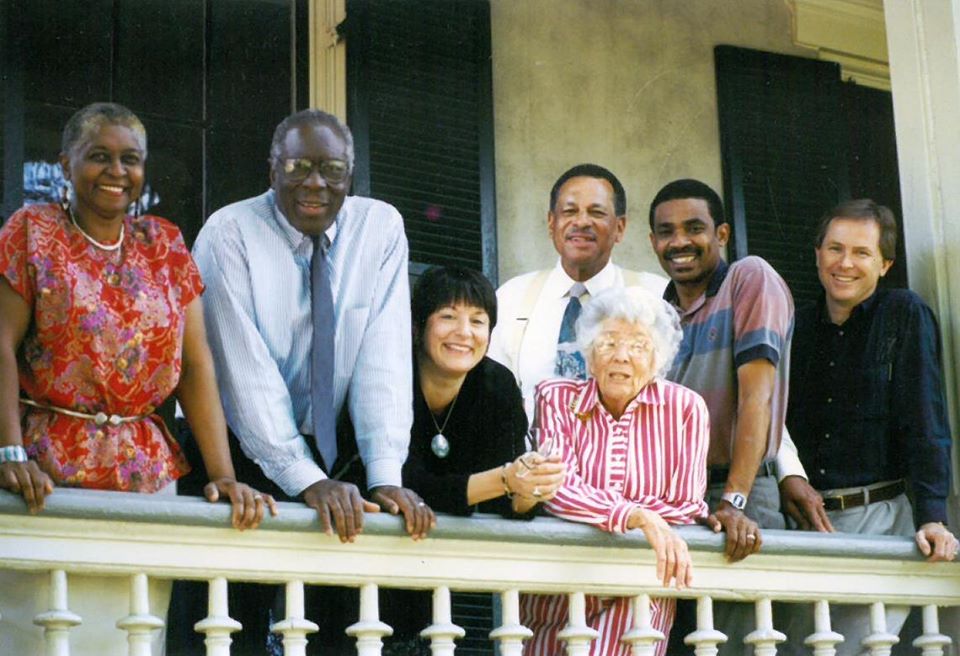

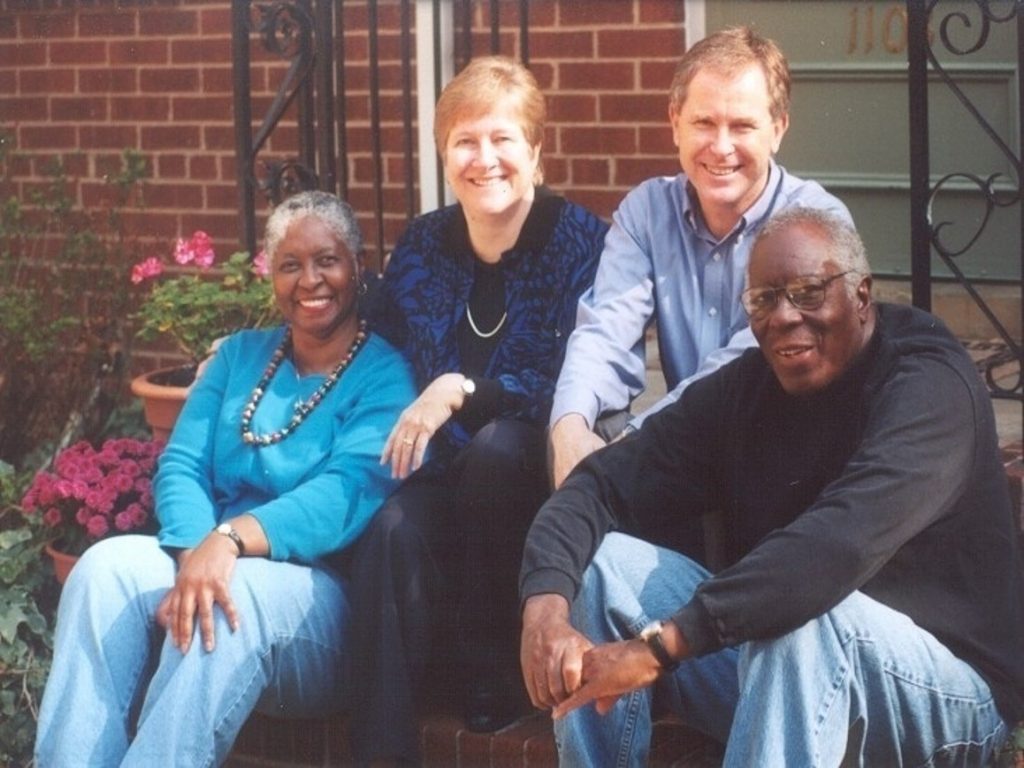

Collie and Audrey encountered Moral Re-Armament (now Initiatives of Change) in 1980 when my wife, Susan, and I moved into a house across the street in the Carillon neighborhood, one of the few racially integrated neighborhoods at the time. As I describe in my book, Trustbuilding, Audrey knocked on our door to welcome us as we were unpacking the boxes. She and Collie were to be our close friends and colleagues for 40 years. The movement that became known as Hope in the Cities began in our two homes as diverse groups of people came together for meals and honest conversation.

When we first came to Richmond people were hesitant to speak openly and honestly about the issue of race. The Burtons were different. As I told Williams, “They brought a directness into the conversations that had been lacking. They felt able to say directly that this is the issue which we have to confront. But they did it with such love and faith in people…It was always an inspirational approach. Collie said, ‘We spend so much effort in changing structures, but we have to keep going back and doing it again, because we did not change the hearts of people.’ He very early on grasped the importance of this connection between personal change and social change.”

“I saw him as a statesman,” Audrey says. “He just was honest and morally upright. He was focused. He had a faith that he believed in, and he defended that faith.” She and Collie were married for 53 years. They met at a National Urban League conference in Atlanta when Audrey was working for the civil rights organization in her home town of New Orleans.

In 1983, William recounts, the Richmonders were invited to take an interracial group to Liverpool, England. “Among the party were the Burtons and A. Howe Todd, then a senior assistant city manager. Collie Burton and Todd had been at loggerheads on different issues. Before the trip, the Burtons invited the Todds to their home and the couple became friends. Upon their return, that friendship ‘rippled through the community’ as people noticed the new relationship and as Black leaders viewed a greater openness in their dealings with Todd.”

By 1993, thanks to the involvement of the Burtons, this network was engaging people of all backgrounds. That year, Hope in the Cities in collaboration with then-Mayor Walter Kenney, hosted the Healing the Heart of America conference and the Unity Walk which publicly acknowledged Richmond’s racial history for the first time. Williams calls this “a remarkable pivot for a city that’d been loath to discuss its brutally racist past. We still have a ways to go in coming to terms with that past, but we’ve moved past silence and denial. It’s difficult to imagine the Richmond of June 2020 without those steps 27 years earlier.” After the Civil War, imposing statues had been erected along the city’s famous Monument Avenue honoring generals and other leaders who had fought to maintain the system of slavery. In 2020, with the support of state and local government and most Richmonders, they were were removed.

“We live in times that test our faith,” writes Williams. “Honest conversations are being drowned out by shouting matches. It’s difficult for some of us to find hope. The changes we see on the horizon cause fear.”

He closes with these words from Allan-Charles Chipman, the executive director of Initiatives of Change USA. “In a political climate in our country where we are invited to degrade our neighbors, we could use more of the spirit of Collie Burton, who lived and taught us to dare to discover the the good in our neighbors. We will continue Collie Burton’s legacy by seeking to engage our community in his spirit for justice, understanding and beloved community. Where there remains spirits dedicated to engaging the world like Collie Burton, there remains a great hope for our city and a great hope in our nation.”

Additional material See PDF of Michael Paul Williams op-ed “A warrior for truth, justice and healing” Richmond Times-Dispatch November 21, 2024. Portrait photo of Collie and Audrey Burton by Rob Corcoran. In addition see this short video by Michael Paul assessing the impact of the 1993 Healing the Heart of America conference and first public walk through Richmond’s racial history.