Watching the moral collapse of the Republican party and the enabling of white nationalism by its leadership, I was reminded that retiring Senator Robert Portman (R-OH) is among those who stand for a very different vision of America. He was one of more than 100 national and local leaders of all racial and political backgrounds who put their names to “A Call to Community” when it was launched at the National Press Club in 1996.

Echoing the theme of Martin Luther King Jr.’s last book, the Call began: “America is at a crossroads. One road leads to community; the other to the chaos of competing identities and interests.… We invite everyone to join us in a renewed commitment to an American community based on justice, reconciliation and excellence.”

The Call was led by Hope in the Cities, a national program of Initiatives of Change, in collaboration with Study Circles Resource Center (now known as Everyday Democracy). The mayors of Baltimore, Atlanta, Jackson, Austin, Cincinnati, and Louisville sent messages. Imam W. Deen Mohammed, spokesperson for the Muslim American Association, and Dr Sidney Clearfield, the international president of B’nai B’rith International, spoke in support. The leaders of the NAACP, Sojourners and the National Conference of La Raza were among the endorsers.

Congressman Dick Chrysler from Michigan, and Senator Gordon Smith of Oregon, both Republicans, as well as former Senator Bill Bradley, a Democrat from New Jersey, signed the Call which was unequivocal in stating the challenge facing the nation: “Much of the distrust, resentment and fear in America today is rooted in our unacknowledged and unhealed racial history…. Because racism is deeply embedded in the institutions of our society, white individuals are often insulated from making personal decisions based on conscious racial feelings…We must change the structures which perpetuate economic and racial separation. But no unseen hand can wipe prejudice away. The ultimate answer to the racial problem lies in our willingness to obey the unenforceable. The new American community will flow from a spirit of giving freely without demanding anything in return.”

Unexpected allies

The previous spring, Bob Webb, a former editorial writer for the Cincinnati Enquirer, had convened a forum in that city with Chip Harrod of the National Conference for Community and Justice. Webb had grown up in Mississippi as a supporter of the racist culture of the time, but a surprising encounter with a Black man had caused him to question his attitudes and then to use his pen “to heal rather than to hurt.” Webb and Harrod invited the mayor, the state treasurer (a Republican), the Episcopal bishop and an Appeals Court judge to meet with leaders of the Hope in the Cities network. Lively discussions led to the first draft of the Call.

Hope in the Cities first tested the Call in Chicago in the fall of 1995. In the Windy City, 150 civic leaders from that city and from other communities came together. Prominent among the 15 alderman who joined the local host committee was Richard Mell, a powerful politician notorious for his opposition to the city’s first Black mayor, Harold Washington. Margaret Palmer, a former speechwriter for Washington, had persuaded Mell to view a documentary film about the first “walk through history” in Richmond, Virginia. Mell was so impressed that he purchased copies to present to Mayor Richard Daley and to all fifty aldermen. He then introduced a resolution to the city council that called the events in Richmond “a remarkable time of healing of the heart and a message for the whole country.” The resolution continued, “If this type of courageous conversation can be done in Richmond, other cities, including Chicago, could begin honest conversation to heal historic wounds.”

Any Republican who signed the Call to Community must be appalled at the current state of their party. As Bret Stephens (a conservative columnist) wrote following the racially motivated mass shooting in Buffalo, “the same Republican party that opposes gun control is also winking at, if not endorsing, the sinister Great Replacement theory – the idea that liberals/Jews/the deep state are conspiring to replace whites with nonwhite immigrants – that appears to have motivated the accused shooter in Buffalo.”

In contrast, the endorsers of the Call said,“We must demonstrate that our diversity is our greatest strength and that out of this diversity will arise a new American community, a community that could be the best hope for a divided world.”

Today about 40 percent of Republican voters say they believe the 2020 election was stolen and efforts are underway in many states to make voting more difficult. Yet, it’s important to remember that throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Republicans were generally more unified than Democrats in support of civil rights legislation. Republicans also strongly supported the Voting Rights Act in 1965, with 30 GOP senators voting in favor. All four reauthorizations of the law, in 1970, 1975, 1982, and 2006, passed the Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support and were signed into law by Republican presidents. In fact, the 2006 reauthorization passed the Senate 98-0. The crisis we face today is one of character, not politics. Racial fear is being used as a means to gain votes. If any reader feels I am being partisan and ignoring the flaws of those on the left, please look at my blog of last July, “Challenges for white liberals.”

A new concept of partnership and responsibility

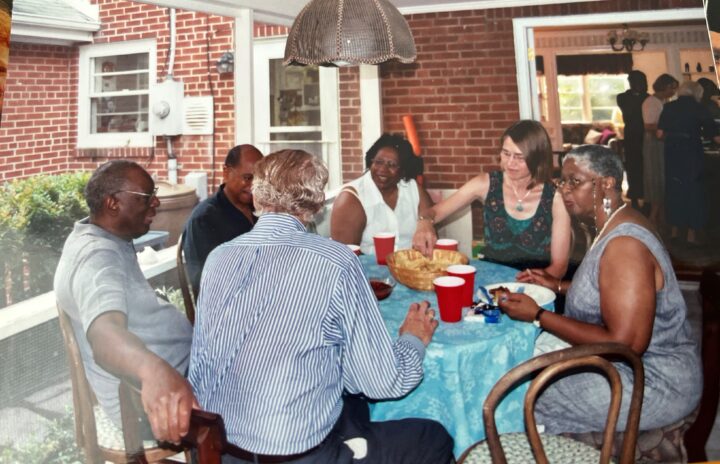

The launching of A Call to Community sparked dialogues, public forums, and actions to acknowledge racial history involving thousands of people of all backgrounds in Richmond (VA), Dayton (OH), Portland (OR), Natchez (MS, Baltimore (MD), and other cities. It coincided with the rapid expansion of similar dialogue models and community actions by other organizations. People found the courage to reach beyond their own group, to overcome their fears and prejudices, and to listen to the stories of others – even those they found difficult to hear. The learning and partnerships from these sustained efforts may prove to be the best hope for America’s future if political leaders are willing to pay attention.

The Call concludes: “To build this new American community, we must empower individuals to take charge of their lives and take care of their communities. In cities across America, bold experiments are taking place. Citizens have initiated honest conversations – between people of all backgrounds – on matters of race, reconciliation and responsibility. This approach calls us to a new concept of partnership and responsibility. It means:

- Listening carefully and respectfully to each other and to the whole community.

- Bringing people together, not in confrontation but in trust, to tackle the most urgent needs of the community.

- Searching for solutions, focusing on what is right rather than who is right.

- Building lasting relationships outside our comfort zone.

- Honoring each person, appealing to the best qualities in everyone, and refusing to stereotype the other group.

- Holding ourselves, communities and institutions accountable in areas where change is needed.

- Recognizing that the energy for fundamental change requires a moral and spiritual transformation in the human spirit.

“Together we will share our lives and the resources God has given us to make America a community of hope, security and opportunity for all.”

Full text of A Call to Community. Full list of endorsers. For a description of the events in Cincinnati, Chicago and at the National Press Club, see Trustbuilding: An Honest Conversation on Race, Reconciliation, and Responsibility by Corcoran