Masks became a divisive symbol over the past two years. Protests erupted across the USA and around the world. Now the masks are coming off. We are emerging, many of us tentatively, into social and workspaces that may feel different. We face everyday decisions, such as when still to wear a mask, whether to shake hands or hug a friend or colleague, as well as what work can be done well online and what requires an in-person setting, the choice of meeting spaces and checking the vaccination status of those in attendance.

There are people in our apartment building who moved in during the pandemic. When I first saw them without a face covering, I did not recognize them. It’s remarkable how a simple piece of cloth can hide our personality and our emotions. During the pandemic we had to learn how to smile with our eyes.

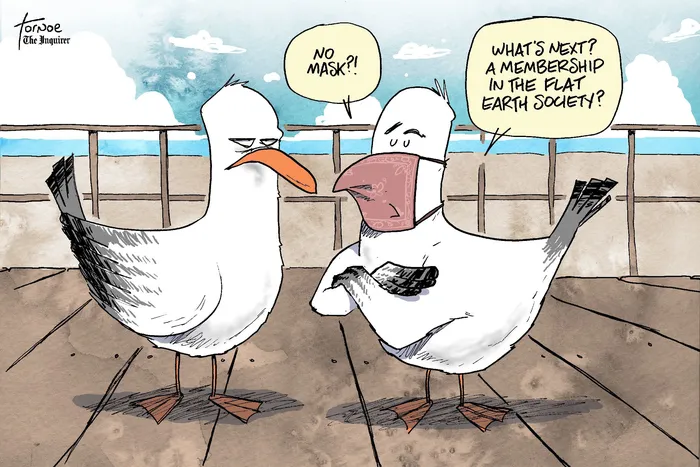

Now that many of us feel free to remove our physical masks – at least in most settings – how much of our real selves are we willing to reveal? Of course, the Internet offers cover for those intent on spreading falsehoods. Social media enables trolls to hide their identities. Anonymous email accounts allow racists to issue threats. Snake oil salesmen can promote their wares without fear of prosecution.

We all like to present the best picture of ourselves. American culture urges us to appear confident and successful. So-called influencers on Instagram are often prime examples of presenting an artificial view of a personality. Here in Texas, the size of a pick-up truck seems to be an important statement of individual freedom.

But in everyday interactions our personal mental masks may hide fear, anger, anxiety, grief, or embarrassment. I served on a committee chaired by a woman who frustrated her colleagues by talking over everyone and pushing her opinions. One day it occurred to me, “Maybe behind what appears to be a dominating personality is insecurity.” I wrote a short note simply expressing my appreciation for her hard work. She replied very warmly, and I noticed a significant change in her behavior. She relaxed. We became good friends, and the committee did excellent work.

Our masks may be unconscious. I worked for many years with a very able African American pastor. One day, after a team building activity, my colleague said, “You know Rob, I think you sometimes withhold your true feelings as a means of maintaining control.” It had never occurred to me that what I regarded as normal Scottish reserve might be interpreted by someone of another culture as a control mechanism. I was always grateful that my friend felt free to make this simple observation without any blame.

Hopefully, I am learning to be more aware of my mental masks. As a facilitator, I’ve discovered that being willing to be vulnerable is an important key to encouraging honest dialogue. People are more interested in hearing about my mistakes than my successes.

Sometimes nations and communities hide from the truth behind a mask.

We tell ourselves stories that protect our pride and dignity and avoid the uncomfortable, painful process of necessary change. For centuries, Britain, my county of birth, developed false narratives that glossed over our history of colonialism, slavery, and racism. As the world watches the horrendous attacks on Ukraine, we can see Putin playing to the grievance, resentment, and lack of respect many Russians feel by promoting false historical narratives about a glorious past.

Since the days of the American civil war, Richmond, and the state of Virginia – where I lived for many years – maintained a mask of “polite silence” about its role in promoting and defending slavery and its leadership in one hundred years of American apartheid. When Hope in the Cities and our allies facilitated the first walk through the Richmond’s racial history, the invitation was signed by a seventy-five-member sponsoring committee comprising the entire city council and boards of supervisors of the surrounding counties, the heads of religious organizations, senior corporate leaders, and directors of grassroots organizations. It stated, “We want to unmask our history together and renounce whatever evil effect it has on us so that God can help us bring justice and healing to our city.”

I came across a column by Paul Graves, a columnist with the Spokesman-Review, who writes, “Authentic, courageous spiritual journeys always involve unmasking our false selves. Doing so helps us experience a vulnerable life-strength found only in the very act of unmasking.”

What do we each need to unmask personally? What are the truths about ourselves, our country and our communities that need to be revealed fearlessly and without blame?