“I refuse to hate someone because they’re Mexican, or because they’re black or white or LGBTQ,” said Tyler Perry in accepting the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at this year’s Academy Awards. “I refuse to hate someone because they’re a police officer or because they’re Asian… I want to take this humanitarian award and dedicate it to anyone who wants to stand in the middle. Because that’s where healing, where conversation, where change happens. It happens in the middle.”

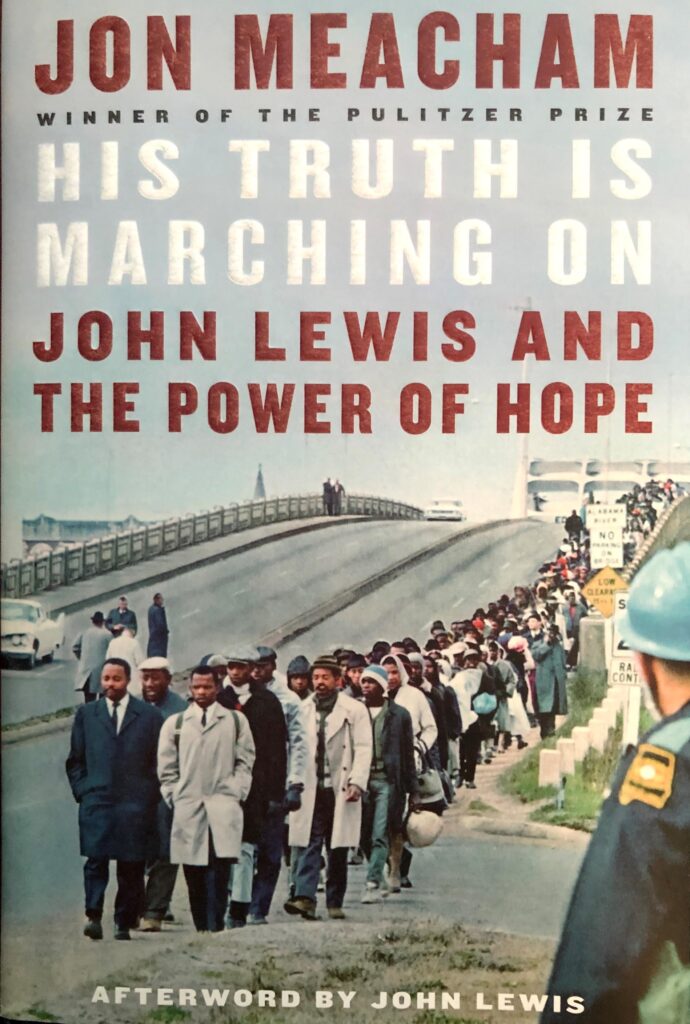

People who refuse to hate and choose to stand in the middle have shown the way to healing and transformative change throughout history. Jon Meacham’s remarkable book, His Truth is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope, spells out Lewis’ commitment to nonviolent resistance and willingness to forgive in the face of white supremist terror. “Within all of us there is a spark of the divine that helps us and moves us,” said Lewis. “This force is part of our DNA.”

Through the influence of people like James Lawson who spent time in India, he came to see that the “Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the Negro in his struggle for freedom….Christ furnished the spirit and motivation, while Gandhi furnished the method.” Describing the struggle for Civil Rights, he said, “We firmly believed we were on God’s side and in spite of everything – the beatings, the bombings, the burnings – God’s truth would prevail.” He was dedicated to Martin Luther King’s vision of the Beloved Community and its practical implications for social justice.

Many others chose a different path. Malcolm X advocated liberation “by any means necessary.” By the mid-60s, the more radical arm of the movement was gaining strength. Lewis’ Christian vision was at once “ inexhaustible and exhausting.” Some described it as “Sunday school piety.” One communication from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) stated, “If we are to achieve true liberation, we must cut ourselves off from white people. We must form our own institutions, credit unions, co-ops, political parties, write our own histories.” Mecham writes, “In the movement circles, the Jim Lawson curriculum of the Bible, Thoreau, Niebuhr, Gandhi and King was being displaced by a 1961 account of the independence struggle in Algeria, The Wretched of the Earth, by Frantz Fanon.” For Lewis, keeping his faith in the vision of the Beloved Community was “the hardest thing in the world.” In many ways he was “an oddity.” He was standing in the middle.

In 1966, Lewis lost the SNCC chairmanship to Stokely Carmichael who believed the time for collaboration with whites was over. “I don’t go along with this garbage that you can’t hate, you gotta love. Man, you can, you do hate.” For Lewis it was a deeply personal loss, although he understood the changing mood. For a while he felt like he was in exile. But he did not respond with bitterness. And although he was devasted by the assassination of Martin Luther King in April 1968, followed just two months later by that of Robert Kennedy, he never lost sight of the vision of the Beloved Community. He remained rooted in his religious faith and the ultimate power of love, and the belief that this vision included everyone, whether black, white, brown, Democrat or Republican.

Creating space for healing and change

As a young shipyard worker who experienced unemployment in the 1930s, my dad was drawn to the work of the Oxford Group (later known as Moral Re-Armament and now Initiatives of Change) by the vision of an alternative to class war – the possibility that new motives in individuals could lead to social justice. Workers and middle-class students formed an unusual team that made a significant impact over the decades on industrial relations in the UK, USA, post-war Germany, Japan, India, and other countries.

I was drawn to Initiatives of Change (IofC) in the 1960s because of its belief that every person can make a difference in the world. My experience has affirmed the claim that change in individuals is the best foundation for sustainable social change, and that God’s guidance, the inner voice, or higher power is a powerful source of guidance and correction. We launched Hope in the Cities in Richmond, VA, in the 1990s as a way for IofC to promote honest conversation on issues of race, reconciliation, and responsibility. We were not an advocacy group. We aimed to illuminate truth and to create space for inclusive dialogue and healing actions without blame or shame. People of all races and social backgrounds had the courage to take a personal inventory of their prejudices or privileges, lay aside their fears, bitterness, or resentments, and walk together with a shared vision.

When I first met Dr. Gail Christopher, she was a senior vice president at the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and was guiding the institution to commit to addressing structural racism as a necessity in its mission to enable vulnerable children to thrive. But I heard her say that being anti-something is not enough. We must be for something. That something was a combination of truth, healing and transformation, and a recognition of the unique value of every human being. At a 2015 conference in Richmond on Healing History: Memory, Legacy and Social Change, she said, “Healing is a process in which we have those rare moments and gifts of awe and appreciation of the perceived ‘other’ and when we see so much more of who we are and what we could be.”

At a time of extreme polarization in America, standing in the middle as Tyler Perry advocates is challenging. Refusing to judge is hard. “Sitting in the fire” to enable truly honest conversation can be intensely uncomfortable. Willingness to risk being misunderstood or criticized by one’s own community requires courage. Recognizing the humanity of every human being may sometimes seem beyond our power. But it is the work that is most needed.