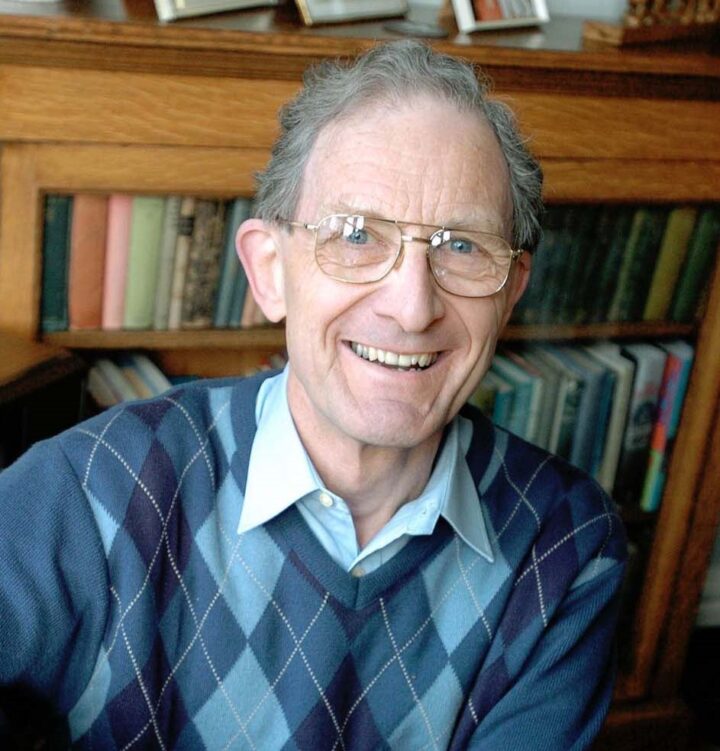

Gerald Henderson was not the most obvious person to lead a movement for truth-telling and racial healing. An Englishman, he was the product, as he put it, of a “white, privileged, middle class, private school background.” Yet he was to become the trusted confidante of people of all races and classes in his adopted hometown of Liverpool, and he played a vital part in the early efforts for honest conversation in a racially divided city like Richmond, Virginia.

Gerald made numerous visits to Richmond (my wife and I moved there in 1980), along with people such as Bernard Gauthier, a senior police prefect from northern France, Hari Shukla, the director of the Racial Equality Council in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne in the UK, and Conrad Hunte, the former vice-captain of the West Indies cricket team. In 1983, he facilitated the visit to Liverpool by a Richmond group on the invitation of Alfred Stocks, the city’s chief executive. This was the first venture outside Richmond for the fledgling team, most of whom had never worked together before.

Collie and Audrey Burton shared the leadership of the group with Howe Todd, the senior assistant city manager, and his wife Joyce, recently retired from teaching at a private school. This in itself was notable because Collie Burton and Howe Todd had a history of sparring publicly on public policy issues. The Burtons and others in the African American community suspected Todd of racially biased views. In Liverpool, the Richmonders met with senior police officers, Marxist militants, elected officials and a leading judge.

Liverpool shares a shameful history with Richmond. Both cities accumulated enormous wealth through the horrendous transatlantic slave trade. Liverpool ships made five thousand crossings. Apparently, Stocks and Henderson thought Richmond might have something of value to share with their city, which had experienced devastating racial violence in 1981 and was deeply divided politically. But the impact on the Virginians was surely greater than the impression they made on Liverpool. The days in Liverpool and the daily interaction with the Burtons marked a turning point for Howe Todd. He began to speak of the need to “build up people, rather than tearing down or criticizing others.” He had learned that “when we talk about problems we must have a spirit of sharing and willingness to hear the other person.”

This new approach did not go unnoticed back in Richmond. A black executive director of a non-profit organization remarked to me, “Howe Todd used to be known as someone who never listened. Whenever I went into a meeting with him, I always felt the cards were stacked, that the decisions were already made. Now he really listens to what I have to say.” The Burton-Todd partnership created ripples throughout Richmond and set the tone for many other connections across traditional divides.

The Liverpool-Richmond collaboration continued for more than two decades. Gerald Henderson was also pivotal in organizing several international cities conferences at the IofC center in Caux, Switzerland. One biproduct was the documentary, “Hope in the Cities” (made by his brother, the journalist Michael Henderson). We adopted that name for the racial reconciliation movement.

In 1993, Gerald and his wife, Judith, who was equally committed to the movement, spent many weeks living in the home of Collie and Audrey Burton as we prepared for the Healing the Heart of America conference, which drew people from some fifty cities and twenty-four countries, and which featured the first public walk through Richmond’s racial history. In the following years, we continued the partnership with the development of the “Reconciliation Triangle” linking Richmond, Liverpool and the Republic of Benin. In 1999, Liverpool’s city council passed a resolution of “unreserved apology” for the city’s role in the trade in human beings and the residual effects on its communities of African descent.

In 2007, led by Governor Tim Kaine, Virginia became the first state to apologize for promoting and fighting to preserve slavery. That year, Gerald brought Liverpool leaders to Richmond for the unveiling of the Reconciliation statue. (Read the full story of the Liverpool-Richmond partnership in Trustbuilding: An Honest Conversation on Race, Reconciliation, and Responsibility.)

Gerald had worked for sixteen years in Africa before he and Judith settled in Liverpool. Their home became a place of hospitality and inspiration for people of all backgrounds. In presenting honorary fellowships to the couple in 2009, Gerald Pillay, the vice-chancellor of Liverpool Hope University, described them as “unpretentious but determined advocates on behalf of the socially disinherited in this city.”

Rev. Ben Campbell, founder of the Richmond Hill ecumenical center and a co-founder of Hope in the Cities writes, “I remember Gerald all the way through the years. What a contribution and dedication! I remember fondly a visit at his house in Liverpool when Paige [Dr. Paige Chargois, one of the visionaries behind the Reconciliation Triangle] and the vice-mayor, Rudy McCollum, and I made a trip to Liverpool. Blessings to all in his honor and memory.”

Some years ago, Gerald described his own learning experience from working with Lawrence Fearon, a British-born community activist of African-Caribbean parents: “Sixteen years living and working in Africa sensitized me to a lot of issues, but it was mainly when I moved to Liverpool following the 1981 riots, in the confrontational climate in the city at that time, that I got actively involved in race relations. I began to realize the degree of pain and sense of exclusion of the racial minorities in this country, not least in that city. Despite all this, it took me quite a while to acknowledge, deep within my own Anglo-Saxon nature, that there was a tendency to control, even though I was not consciously aware of it.

“It has been, in part, with Lawrence’s help, that I have realized that it is often not just conscious racism but deeper factors of control that people like me are often unaware of that destroys trust. Fear is certainly one factor that breeds control, not necessarily fear of what others will do, but wanting to keep things on track, on your track… I can only help others if I recognize it in myself. Lawrence and I try to keep short accounts and are transparent about these matters, because we need to mirror the trustbuilding work we feel called to do in the community.”

Gerald died peacefully at his home on September 25. He was a humble, unfailingly gracious man. In my book I write, “Trust depends on the authenticity of our lives, our openness and our willingness to start with change in ourselves.” Gerald was an authentic person who walked the talk.