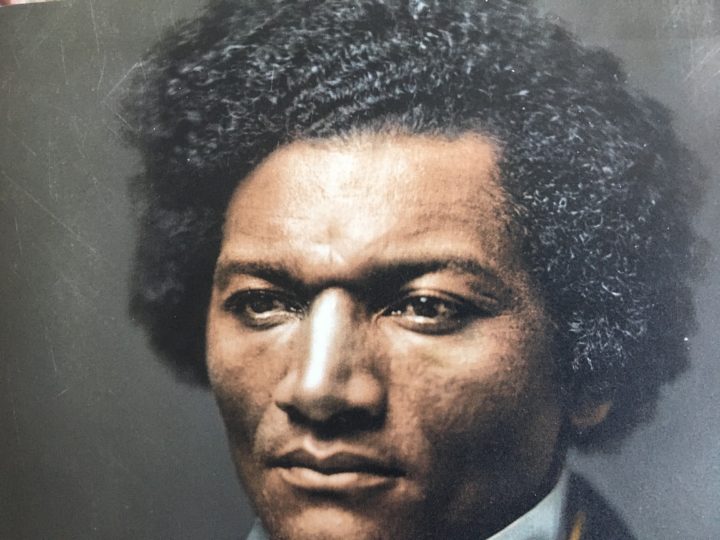

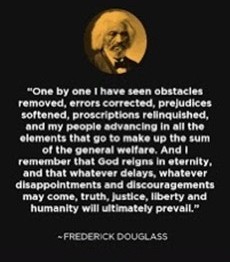

In the summer of 1852, Frederick Douglass delivered one of the greatest speeches in US history. Just two years earlier, Congress had passed the Fugitive Slave Act which required that escaped slaves be returned to their owners even if they were in a free state. Douglass himself had escaped from slavery in Baltimore, Maryland just fourteen years earlier to become one of the most powerful and eloquent voices for abolition. Despite his fury at slave holders and his biting condemnation of the hypocrisy and complicity of the Christian church, Douglas articulated a prophetic vision for America.

He called the Constitution a ”GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT” full of “principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.” He rooted his hope in three elements. First, the antislavery interpretation of the Constitution. Second, his belief in divine Providence, in the idea that a moral force would in the end govern human affairs. And third, he appealed to the “tendencies of the age” to modernity, describing the remarkable advances in education, commerce, transportation and communications. “Oceans no longer divide, but link nations together. Space is comparatively annihilated.” He urged the nation to keep faith; slavery could not hide from “light” itself.

Douglass described the “Slave Power conspiracy” as not just as a moral wrong against black people but as a widening threat to the liberties of white people. And he promised to attack racism in the North with equal fervor.

David Blight’s superb biography of Douglass, which inspired this blog, highlights the young abolitionist’s remarkable faith in light of the dire national situation. Both major parties in Washington were sacrificing their integrity for political gain and the Supreme Court was to rule two years later in the Dred Scott decision that Americans of African descent, whether free or slave, could not be American citizens and that none of the rights and privileges the Constitution confers on citizens could apply to them. Chief Justice Taney went further to declare the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional and that Congress had no right to regulate slavery in the territories, implying that slavery could become legal throughout the nation. Yet Douglass asserted that Taney could not change the essential law of nature by making evil good and good evil. Freedom has the “laws which govern the moral universe on its side.”

Time and again he returned to the bible and the prophets as his source of hope and affirmation of God’s plan. “…he will faithfully bring forth justice. He will not grow faint or be crushed until he has established justice on this earth. (Isiah 42)

Those of us today who are tempted to lose heart at the lack of moral courage in Washington or the growing racial polarization and xenophobia across the country might gain new perspective and hope from Douglass who was living in far darker circumstances.

One hundred years later, Martin Luther King, Jr. whose life and vision we celebrated a few weeks ago, drew inspiration and courage from the same biblical source as Douglass. He was a truth teller who constantly called on America to be her best self.

Joel Edward Goza writes in the publication Salon that in the years following King’s “I have a dream speech” the country saw historic progress in civil rights, voting rights and actions to fight poverty. Yet, in the midst of this progress, “old wounds and racist ways of thinking exploded, entrenching racial and economic inequalities all the deeper. Race riots lit by long-held rage over brutal discrimination burst black communities into flames, and white backlash inspired by the civil rights legislation began radicalizing racist voting patterns among dis-eased whites. When King aimed to address northern styled segregation and close economic gaps for the working poor by demanding capitalism to negotiate with human dignity, repeated failure replaced repeated victories. With the nation in flames and his movement out of water, King then watched as Vietnam ate up America’s mind, bodies and spirit. The Samson of the Civil Rights struggle was, so to speak, going bald, and King watched his dreams begin to descend into a nightmare.”

But Goza says, “What struck me in this era was how his disillusionment with America’s addictions neither discombobulated nor tamed his moral vision or his hopes. His vision for our nation refused to conform to the compromises of the day and in the darkness his vision grew clearer.”

Congressman John Lewis writes in Time, “Of all the gifts given us by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., I think the greatest has been the belief in society’s ability to change and the power each of us has to affect that change.”

Faith, hope and love are powerful resources for change. Despite the headlines and social media chatter, countless thoughtful conversations are taking place every day that bring people together, countless individual relationships are being built, countless acts of courage and selflessness continue to weave the fabric of community.

My wife and I took part in a conversation about resilience organized by The Red Bench, a program of Interfaith Action of Central Texas. Groups of complete strangers sat around tables and shared often quite personal perspectives and stories. Several people referred to some daily spiritual practice or discipline ranging from meditation and prayer, to walking, art and expressions of gratitude as ways to build resilience. Frequently, the word “hope” was mentioned as a key factor. It was a simple one-hour conversation, but it was surprisingly meaningful. At the end one woman who had come carrying a burden of deep family concerns said, “I feel renewed.”

How important that simple word hope is. When we began our racial reconciliation work in Richmond, Virginia we chose to call the emerging movement “Hope in the Cities,” not Hope for the Cities. It was a deliberate choice of words. We believed that hope was already present in the community and that our job was to call it out and to encourage the best in those abound us. At the time few people could have imagined that Richmond might become a seedbed for honest dialogue and racial healing. But hope is infectious, and it gives energy.

One of the resilient pioneers of the Richmond Hope in the Cities movement is Audrey Burton. She and her husband were community organizers who led the voter registration drive which resulted in the first black majority on Richmond’s city council in 1977. She says, “Hope is spiritual and social. It’s not just futuristic. It is a powerful word and concept. The more we say it, the more we become it. This is an identity for us. We become hopeful in a spiritual sense and we apply this identity in the social fabric of this community.”