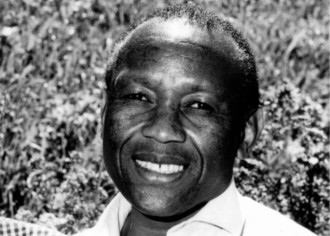

This is a tribute by Pieter and Meryl Horn to their fellow South African Sam Pono who passed away on September 25. My wife Susan and I had memorable experiences with Sam in 1977 during the depth of apartheid when we took part together in the musical production referred to in this story, in the early 90s as the country emerged as a democracy, and during a sabbatical in 2005. He was a treasured friend, a warrior for racial truth and healing, and a fellow musician (see us in photo above).

JAZZ MUSIC resounded around the hall at the memorial service for Sam Mxolisi Pono, enthusiastically rendered by the band whom Sam used to play his saxophone with. There were saxophones, drums, a keyboard, clarinet and a trumpet (played by Soyisile Pono).

Sam Mxolisi Pono was born in Queenstown, now called Komani, on December 10, 1942. He was musically gifted and became part of the ‘Modern Jazz Sextet’. They were in great demand in nightclubs. Sam’s day job was with a furnishing company.

Soyisile, Sam’s eldest son, said that his father ‘grew up in a family where music filled the air.’ Life was not easy and there were few opportunities, but they had the passion, sometimes sharing instruments. ‘What made my Dad extraordinary,’ said Soyisile, ‘was not just his talent but his honesty and his courage to face himself. Like many of his generation he faced difficult challenges, but he never allowed them to define him. That took strength, quiet steady, powerful strength. He taught us that a man is not made perfect by never failing, but by rising again and again with grace and truth.’

As he grew up, Sam became more politically conscious and anti-white. Through a social worker in Queenstown, Mrs Eginah Mzazi and a white Karroo sheep farmer, Colin Bowker, Sam met the work of Moral Re-Armament, now Initiatives of Change. Miss Mzazi said to Sam, “I feel certain qualities in you which can contribute to the nation if harnessed rightly. But if wrong forces grip you, or you continue to destroy yourself with liquor and women, all that will be lost.”

Sam responded to this. He was honest with his father about his salary and the fact that he was not declaring his full income to his father and the home. His father then said, “I must be honest too. I have not been bringing all my money home either.” “It built a new family because my brothers and sisters had been copying me,” said Sam.

In 1973 Sam spent time overseas, not for personal gain, ‘but to listen, to learn and understand how people around the world were healing from division,’ said Soyisile, speaking at the memorial. As Sam travelled he felt God gave him a clear commission. First was to care for those from all over Africa. Secondly, was to care for the descendants of the slaves who were taken from Africa.

In the United Kingdom he made friends with Afrikaner Rhodes Scholars in Oxford and black South African exiles. He met trade unionists and their families, Communists, Capitalists and even a Prime Minister.

Conrad Hunte, Vice Captain of the West Indies cricket team, invited him to go with him to the West Indies. He told Sam that it may take 7 – 10 years to learn to be effective in the ideological battle for nations and that he must stand on his own feet before God. Sam said, “This was a great lesson for me. You can easily become a puppet, whether it’s of another man, or of Marx, or Mao or any leaders. We need the kind of independence in Africa where we are free, not just of domination by whites but of dependence on other men. Then we will have people who can be trusted to do what is right. Through all my experiences I have learnt that the ordinary man can be used by God in an extraordinary way.”

Sam returned to South Africa in 1976. He started off by living at the Moral Re-Armament centre called Lawley Road, in Johannesburg. This is where Sam and Pieter Horn, friend and colleague met for the first time.

The Soweto Uprising

Pieter says, “Following the Soweto ‘Uprising’ in 1976, the Soweto Committee of 10, headed by Dr Nthato Motlana, a medical doctor in Soweto, was established. It took control of Soweto. Earlier Sam and I had had the opportunity to meet with the Chief Communications Officer for the West Rand Administration Board, Jan Bosman. He told us that he had been sent by the police to fetch Dr Motlana and two others who had been imprisoned due to their Soweto Committee of 10 activities and were now released and needed to be taken to their homes in Soweto. Jan, regarding them as ‘terrorists’ and ‘communists’, was dead scared, but the thought kept coming to him to ask them if he could pray for them and the country. Eventually, Bosman found the courage to ask them if he could pray. They cheerfully agreed and Bosman prayed, but, as he told us later, ‘with one eye open in-case they beat him up and took his car to join the liberation movements in neighbouring Mozambique.’ Bosman described Motlana as a very difficult man to deal with in the administration of Soweto.”

Pieter continues: “Hearing this from Jan Bosman, Sam and I had the thought to go and see Dr Motlana at his medical practice in Dube, Soweto. We did not make an appointment but simply joined the queue of patients in his surgery. When there was no-one ahead of us, we walked into his office and told him about the work of MRA in working for racial reconciliation and how the two of us had to talk out issues between us in a blunt and honest way. ‘Is this the way you talk to each other?’ he asked when we had finished talking.

“The next thought we had was to invite Dr Motlana and Jan Bosman to a dinner at the MRA home in Johannesburg. The conversation around the dinner table was very polite but no serious issues were raised. Over a cup of coffee, we showed them the film, Chapter and Verse, an interview with Conrad Hunte on Scottish TV. Sam then suggested we have a time of silence. After some of us said a few things, Bosman said that during the time of quiet he prayed for God to change Motlana –then he had the clear thought, ‘Leave Motlana to me, you are the one to change!’. Motlana responded saying that, ‘If I have to talk in the spirit of this evening, it will not be about politics but about my concerns and wishes for my three sons.’

“The outcome of the evening was that a trust was built between these two men and they decided to meet regularly at the ‘Rose Bowl’ in Soweto to try to resolve issues between Committee of 10 and West Rand Administration Board.”

Time to Choose

In 1977 a group of young people from all over the world with a musical called Time to Choose, visited South Africa and Rhodesia. “Sam, playing the saxophone in the band and Nombulelo Khanyile, and my wife and I joined the group,” said Pieter. “On our way to Cape Town we had to stay one night in a hotel in Colesberg due to transport problems. Conrad Hunte, being an overseas visitor, was given a room in the ‘whites only’ part of the hotel. Sam being a Black South African, was relegated to servants quarters. Conrad tried to fight this injustice and in the end, went and joined Sam in the back room, with tattered sheets on the beds.”

Later, in 1977 Sam and Pieter were introduced to the Mashinini family in Soweto. Tsietsi was one of the initiators of the Soweto youth uprising of 1976. Pieter continues, “Sam and I started lobbying politicians, taking young black activists to meet Members of Parliament and Cabinet Ministers, including Roelf Meyer who played a key role in the Codesa negotiations during the transition period from Apartheid South Africa leading to the first fully democratic elections in 1994.

“Working with Prof Cornelius Marivate, a Professor in African Languages at University of South Africa (UNISA), we got to know a number of young Black activists from Atteridgeville, Pretoria. In 1978 Sam and I took a group of them to Rhodesia where we met a cross-section of people ranging from white politicians and black nationalists involved in the liberation movements. We shared our stories of change and trust building. We were even asked to visit a military base in Bulawayo. On our return we were questioned by the South African Security Police at Beitbridge border-post, vehicle searched, papers confiscated etc. and eventually released after about 8 hours. Some of these young men later became involved in the liberation struggle in South Africa.”

Sam served as a voluntary member of the Council of Management of Moral Re-Armament, South Africa, now called Initiatives of Change as well as being Chairman of the Board for a number of years.

Compassion, commitment and clarity

Pieter notes that Sam never went anywhere without his saxophone. “On one of our many visits to Zimbabwe during the 1980s, Sam was keen for Rev. John Burrell and I to meet his future wife Virginia and her family, in Bulawayo. During the introductions and conversation with Virginia and the family, we asked Virginia whether she had ever met Sam’s ‘other wife’, meaning his saxophone. After a stunned silence we had to explain and apologise. The conversation continued and Sam did marry Virginia. A year or so later, Meryl and I attended Sam and Virginia’s wedding in Bulawayo/Zimbabwe.”

Later Sam and Virginia decided to make their home in South Africa. On their way south from Zimbabwe, they were arrested by the Zimbabwean security police at Beitbridge border post, falsely accused of spying for the South African Apartheid Government. After a week under police guard at Beitbridge, Virginia was released. Sam was taken to the notorious maximum security prison, Chikurubi, in Harare. Sam’s torture while in Chikurubi had a severe effect on him health-wise and emotionally.

He was eventually released after much pressure from prominent international figures such as Conrad Hunte; Prof Rajmohan Gandhi, grandson of Mahatma Gandhi; Allan Griffith, Advisor to the then Australian Prime Minister; Atlanta USA Mayor Andrew Young, and Ambassador Archie Mackenzie (UK).

After two strokes and a long battle with ill health, Sam Mxolisi passed away on September 25, 2025, at the age of 83. Messages from all over the world are testimony to Sam’s love and compassion for people. Many mentioned his jolly laugh, his musical talent, his humility and his obedience to the God he love and served.

Soyisile shared, “Dad cared particularly about those who were overlooked. He did not shout. He did not seek the spotlight. He just did the work with compassion, commitment and clarity. At the heart of everything he was a family man, building a family home grounded in love and respect.

Our thoughts remain with Sam’s family. His wife Virginia, and children, Dudu, Vuyokazi, Soyisile and Mashudu and grandchildren. May you be comforted by God’s love for you.

Excerpts from Southern Africa What Kind of Change? by Peter Hannon. Available on foranewworld.org

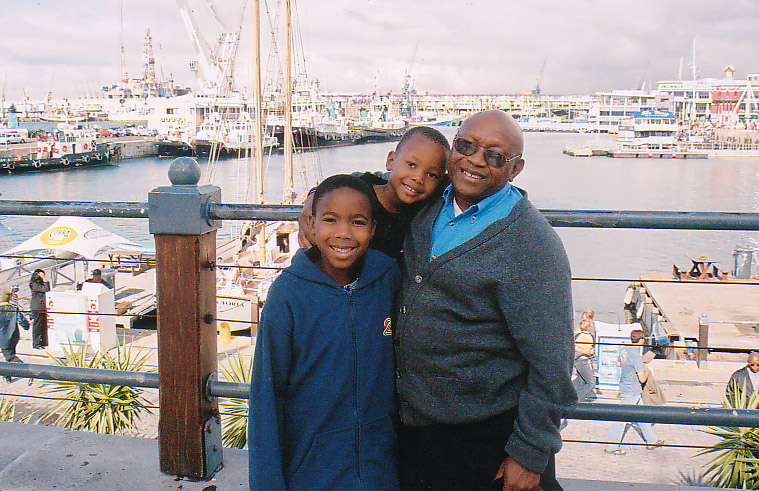

I have added some photos that I took during our 2005 sabbatical

Top: Sam and Virginia, and Sam and their two boys in 2005. Below (left): with police inspector Kevin Williams at a community event in the colored community in Cape Town, and (right) renowned peace scholar Janie Malan.