Two pioneers of Hope in the Cities (Initiatives of Change USA) left us in recent weeks. Jesse Frank Williams, III, (Jeff) was one of the first people I got to know when my wife and I moved to Richmond, Va, in 1980. He became a trusted friend and an ally in the work of honest conversation on matters of race. The Rev. Dr. Paige L. Chargois was a close colleague who served with me as assistant national director of Hope in the Cities (HIC) and played a key role in our work locally, nationally and internationally. Jeff and Paige will long be remembered as individuals who helped Richmond face its painful past. They personified the new spirit that Hope in the Cities brought to the city and paved the way for a process of healing and trustbuilding in communities across America and the world.

Jeff was born in Clarksburg, West Virginia. He had a talent and passion for commercial real estate, and he spent almost 45 years at Harrison & Bates as a broker, developer, president and chairman of the board. He also served as President of the Richmond Board of Realtors and on many other community boards and associations. Jeff was a generous financial supporter of HIC and at one point co-chaired its Advisory Council along with Audrey Brown Burton, a leading Black community activist who worked in the Virginia Department of Corrections (and later New York), and in whose home much of the early work of HIC began.

I met Jeff when I joined a men’s group that met every Wednesday morning at the United Virginia Bank for a time of spiritual reflection. Our host was John Robertson, the executive vice president of the bank. Most of the attendees were white businesspeople, an interesting learning experience for me as a social democrat and the son of a lifelong warrior in the international labor movement. An unexpected and unique presence was John Coleman, a Black lay preacher who ran a center for underserved communities. It was from John that I learned a life lesson: “The bridge of trust must be strong enough to bear the weight of the truth you are trying to communicate.” Another participant was Frank Mountcastle, Jr., the vice president of NationsBank (now Bank of America). Frank became the treasurer of HIC. He wrote of Jeff, “You can take Jeff out of West Virginia, but you can’t take West Virginia out of Jeff! The ‘Clarksburg flash ‘ who loved to win, on the basketball court and also the pool table….a strong and athletic competitor, also in life where he took comfort in knowing he had somewhere to go when his earthly life was over.” Frank recalled that Jeff had also co-chaired the HIC council with Eric Armstrong, a Black Richmonder and owner of an insurance business. “I loved the banter between Jeff and Eric as they co-chaired our work together, with smiles and good-natured ribbing.” The Rev. Robert Hetherington, a longtime Wednesday group member and staunch HIC supporter, wrote about Jeff: “He never lost his congenial spirit as he declined.”

Our conversations in the group were often wide-ranging, and I found I could learn much from those of different social backgrounds or with different political viewpoints. Jeff and Frank’s prominent role with Hope in the Cities helped give credibility to our work with the business community. As a result, we were able to hold annual Metropolitan Richmond Day breakfasts with hundreds of people from all sectors of the community who bought tickets while the banks and other businesses sponsored tables – a significant support for our program. Jeff died on July 6.

Paige L. Chargois, joined Jeff in the next life on July 27. Paige was a powerful and unique personality. A Baptist minister with a gift for expression (she became an Episcopalian for the last phase of her faith journey), Paige played a major role in developing the vision for Richmond’s first walk through its racial history at the Healing the Heart of America conference in 1993. She understood the power of story and historical narrative. She said, “Facts have emotional components which are attached to our hearts. We need to look within the ‘package of pain’ because ultimately, it’s not the facts that challenge us…it’s the pain we choose not to get beyond.” As she reflected on the work of healing for the Richmond community, Paige concluded, “By acknowledging the wrong and taking responsibility as a community, we begin to be the answer….We can say to each other, ‘Not only is the problem in us but the answer is also in us.’”1

Paige served with me on the city’s Slave Trail Commission created after the 1993 conference. She was a leading visionary behind the “reconciliation triangle” linking Liverpool, UK., the Republic of Benin, and Richmond, all of which were deeply involved in the transatlantic slave trade. In December 1999, Liverpool city council issued a public apology, and that later that month President Matthieu Kerekou of Benin convened representatives of the international diaspora when he apologized for his ancestors’ role in selling fellow Africans. Liverpool donated to Benin a full-scale replica of a sculpture by Liverpool artist Stephen Broadbent entitled “Reconciliation”.

After seeing the statue during an official visit to Liverpool with Richmond’s vice mayor Rudolph McCullom, Paige reported to the Slave Trail Commission, and the city allocated city funds for a second copy to complete the triangle in Virginia. On March 30, 2007, three thousand people celebrated the unveiling of the Richmond statue in the presence of the ambassadors of Benin, Gambia, Niger and Sierra Leone and a delegation from Liverpool. One month earlier, Virginia had become the first state in the nation to offer an official apology for its role in maintaining and defending slavery. At a landscaped plaza near the former slave market, water flows over a map depicting the transatlantic trade. An inscription acknowledging the suffering of millions of Africans who were transported from their homeland, concludes, “Their forced labor laid the economic foundations of this nation.”

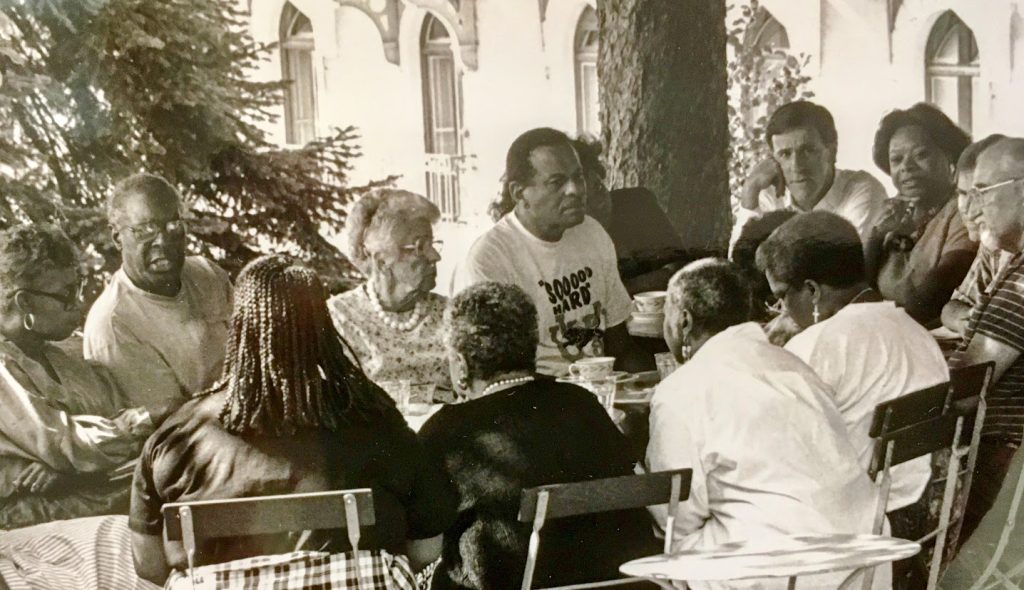

Remarkably, Paige reached out to a leader of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, an association for female descendants of Confederate soldiers who fought in the civil war to preserve the right of southern states to maintain slavery. Formed in 1894, it focuses on commemorating Confederate ancestors, building monuments, and promoting the “Lost Cause”. This difficult but for Paige life-changing experience between two women “living out the shared legacies of pain in the soul of the nation’s experience” is described in detail in Trustbuilding. Paige also built a relationship with the local president of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, even inviting him to the IofC conference center in Caux, Switzerland.

In December 1997, as Hope in the Cities’ reputation grew nationally, Paige and I were invited to join a small team charged with designing a dialogue guide for President Bill Clinton’s race initiative.

One special memory stays with me: In the summer of 2002 Rev. Dr. Syngman Rhee addressed the IofC international conference in Caux, Switzerland. As he approached the podium, the Korean-born peacebuilder and respected leader of the Presbyterian church (USA), removed his shoes. He explained “I am deeply honored to be on this ‘holy ground’ at Caux where so many people have dedicated their lives to reconciliation, peace and justice for all humankind throughout the world.” Paige, who had invited Rhee to Caux, rose from her seat, and placed her own shoes at the foot of the platform. Many others followed suit until there was an array of dozens of shoes of all shapes, sizes and colors.2

Thank you, Jeff and Paige. I know you will continue to bless this work from above.